IT IS going to be a great opportunity—but whether an opportunity for business innovators or for rent-seekers and scam-merchants depends on whom you ask. On January 12th ICANN, the body that regulates the naming system of computers connected to the internet, starts accepting applications for new generic top-level domains (gTLDs). There are currently just 21 of these (22 if you count .arpa, used only for managing the internet's technical infrastructure), and most are reserved for specific users: .edu for American universities, .aero for air-transport companies, the recently-launched .xxx for pornography purveyors, and so on. Only four—.com, .org, .net and .info—are open to anyone. Website owners with global pretensions often prefer them to country-code TLDs such as .uk, .ru and .cn (though some of those, like Tuvalu's .tv, have become internationalised). And they are getting a little crowded.

So now anyone with the money (at least $185,000 up front, plus maintenance fees starting at $6,250 a quarter) can apply for a new top-level domain like .beaches, .porn or .tango, from which the owner can then license the subdomains (mexico.beaches) to other people. There will be safeguards to protect trademarks like .canon or .siemens; generic domains like .lawyer or .bank will be reserved for organisations that can prove they represent substantial parts of the community of lawyers and bankers; and someone who wants a geographic name like .london or .berlin will need to have a green light from the local authorities.

There is a mad rush: up to 1,500 applications are expected in this first round. ICANN, a bureaucratic non-profit body which set the fees on the basis of what it cost to process ten gTLD applications in 2003, is going to have to scale up fast. (Expect the fees to come down as it does so.) America's Federal Trade Commission stopped short of blocking the gLTD expansion but sent ICANN a stiff letter warning it that it is opening the floodgates to a tide of legal disputes, racketeers and technical snafus that it is ill-equipped to handle.

But even leaving those problems aside, it is still pretty unclear what the benefits will be. Here are some of the purported ones, as described by Theo Hnarakis of Melbourne IT, a company that has snagged over a hundred would-be gTLD registrants as its clients:

-

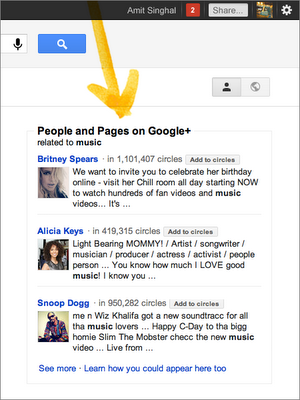

Navigation. People will remember addresses like ipad.apple more easily than ipad.apple.com. This means they are more likely to type the address straight in rather than searching for "Apple iPad", which is good for Apple because if they search, they might click on another link or on a sponsored Apple link which then costs Apple money.

-

Search. Search will work better, because ipad.apple will come in among the top results for "apple ipad".

-

Security. It is easy to send people "phishing" e-mails from plausible-sounding addresses like info@citibank-cards.com or info@invest-hsbc.com, which dupe them into clicking on links and revealing passwords or other information. But if you see an e-mail ending in .citibank, you will know that only Citibank could have sent it.

-

Geographic specificity. Your favourite restaurant's website may well be something like janesmithnyc.com. If it could be janesmith.nyc, then Jane Smith's in London could be janesmith.london, and so on. Moreover, the new gTLDs can be in non-Latin script, adding to the diversity.

-

New business models. A company—British Airways, for instance—could buy .holidays, and license its subdomains (caribbean.holidays, etc) to other travel companies—or keep them all for itself, so that it bags all the search traffic. According to Jason Rawkins, an intellectual-property lawyer at Taylor Wessing, investment funds have already been created to buy portfolios of gTLDs for licensing.

It should be obvious that there are a lot of untested assumptions here. Does taking off a .com really make web addresses easier to remember? After all, the .com hardly varies; it's the rest of the address you have to guess at. Things could in fact get more complex, not less. Right now you can guess that a company's web address is probably companyname.com, but .companyname alone can't be a web address. So will Microsoft's home page be home.microsoft, www.microsoft, main.microsoft? Will Air France choose home.airfrance, accueil.airfrance, vols.airfrance?

On the security front, is educating people to trust only e-mails from info@cards.citibank really any easier than educating them to trust only info@citibank.com? For a small business, a website like janesmith.nyc may be a boon—but does the Nobu restaurant chain, with branches in two dozen cities in over a dozen countries and growing, really want the hassle of buying and maintaining separate subdomains from the registrars of each one just so it can have nobu.miami and nobu.moscow (to say nothing of nobu.москва and нобу.москва), rather than managing them all through one website as noburestaurants.com/miami and so on?

There is clearly lots of scope for abuse—such as cybersquatting, the practice of buying up domain names in advance and forcing those that really want them later to pay through the nose—though ICANN has tried to pre-empt this with its dispute-resolution procedures. But there is also scope for plain old aggressive business practices that smack of anti-competitiveness. (Why should other companies that sell Apple products be squeezed out of search results in favour of Apple? Why should one airline nab more holiday-makers than another just because it bought .holidays first?)

A lot of these problems can be fixed, of course, with a bit of work. Registrars can create lots of variants of a web address that will redirect to one of them (home.microsoft). An intermediary can offer Nobu a one-stop service for managing all its geographic domain registrations. Lawyers will handle the dispute-resolution and the negotiations over licensing second-level domains. Which is why Esther Dyson, a technology entrepreneur who was the founding chairwoman of ICANN, launched a broadside at the idea last summer. It will, she wrote, "create lots of work for lawyers, marketers of search-engine optimisation, registries, and registrars. All of this will create jobs, but little extra value."

It is true that opening up gTLDs is probably unavoidable: just think of all the Jane Smiths, Mohammed Husseinis and Li Wens out there who will be wanting websites in the future. But Ms Dyson may well be right that the chief beneficiaries will be those who profit from untangling the mess.