Digital Life: Today & Tomorrow

15 keys facts and conclusions to know the future of the Internet in 2015.

A COUPLE of weeks ago, I replaced my three-year-old BlackBerry Pearl with a much more powerful BlackBerry Bold. Needless to say, I was impressed with how far the technology had advanced in three years. Even when I didn’t have anybody to call or text or e-mail, I wanted to keep fondling my new Bold and experiencing the marvelous clarity of its screen, the silky action of its track pad, the shocking speed of its responses, the beguiling elegance of its graphics.

Illustration by Sarah Illenberger, Photograph by Ragnar Schmuck

I was, in short, infatuated with my new device. I’d been similarly infatuated with my old device, of course; but over the years the bloom had faded from our relationship. I’d developed trust issues with my Pearl, accountability issues, compatibility issues and even, toward the end, some doubts about my Pearl’s very sanity, until I’d finally had to admit to myself that I’d outgrown the relationship.

Do I need to point out that — absent some wild, anthropomorphizing projection in which my old BlackBerry felt sad about the waning of my love for it — our relationship was entirely one-sided? Let me point it out anyway.

Let me further point out how ubiquitously the word “sexy” is used to describe late-model gadgets; and how the extremely cool things that we can do now with these gadgets — like impelling them to action with voice commands, or doing that spreading-the-fingers iPhone thing that makes images get bigger — would have looked, to people a hundred years ago, like a magician’s incantations, a magician’s hand gestures; and how, when we want to describe an erotic relationship that’s working perfectly, we speak, indeed, of magic.

Let me toss out the idea that, as our markets discover and respond to what consumers most want, our technology has become extremely adept at creating products that correspond to our fantasy ideal of an erotic relationship, in which the beloved object asks for nothing and gives everything, instantly, and makes us feel all powerful, and doesn’t throw terrible scenes when it’s replaced by an even sexier object and is consigned to a drawer.

To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.

Let me suggest, finally, that the world of techno-consumerism is therefore troubled by real love, and that it has no choice but to trouble love in turn.

Its first line of defense is to commodify its enemy. You can all supply your own favorite, most nauseating examples of the commodification of love. Mine include the wedding industry, TV ads that feature cute young children or the giving of automobiles as Christmas presents, and the particularly grotesque equation of diamond jewelry with everlasting devotion. The message, in each case, is that if you love somebody you should buy stuff.

A related phenomenon is the transformation, courtesy of Facebook, of the verb “to like” from a state of mind to an action that you perform with your computer mouse, from a feeling to an assertion of consumer choice. And liking, in general, is commercial culture’s substitute for loving. The striking thing about all consumer products — and none more so than electronic devices and applications — is that they’re designed to be immensely likable. This is, in fact, the definition of a consumer product, in contrast to the product that is simply itself and whose makers aren’t fixated on your liking it. (I’m thinking here of jet engines, laboratory equipment, serious art and literature.)

But if you consider this in human terms, and you imagine a person defined by a desperation to be liked, what do you see? You see a person without integrity, without a center. In more pathological cases, you see a narcissist — a person who can’t tolerate the tarnishing of his or her self-image that not being liked represents, and who therefore either withdraws from human contact or goes to extreme, integrity-sacrificing lengths to be likable.

If you dedicate your existence to being likable, however, and if you adopt whatever cool persona is necessary to make it happen, it suggests that you’ve despaired of being loved for who you really are. And if you succeed in manipulating other people into liking you, it will be hard not to feel, at some level, contempt for those people, because they’ve fallen for your shtick. You may find yourself becoming depressed, or alcoholic, or, if you’re Donald Trump, running for president (and then quitting).

Consumer technology products would never do anything this unattractive, because they aren’t people. They are, however, great allies and enablers of narcissism. Alongside their built-in eagerness to be liked is a built-in eagerness to reflect well on us. Our lives look a lot more interesting when they’re filtered through the sexy Facebook interface. We star in our own movies, we photograph ourselves incessantly, we click the mouse and a machine confirms our sense of mastery.

And, since our technology is really just an extension of ourselves, we don’t have to have contempt for its manipulability in the way we might with actual people. It’s all one big endless loop. We like the mirror and the mirror likes us. To friend a person is merely to include the person in our private hall of flattering mirrors.

I may be overstating the case, a little bit. Very probably, you’re sick to death of hearing social media disrespected by cranky 51-year-olds. My aim here is mainly to set up a contrast between the narcissistic tendencies of technology and the problem of actual love. My friend Alice Sebold likes to talk about “getting down in the pit and loving somebody.” She has in mind the dirt that love inevitably splatters on the mirror of our self-regard.

The simple fact of the matter is that trying to be perfectly likable is incompatible with loving relationships. Sooner or later, for example, you’re going to find yourself in a hideous, screaming fight, and you’ll hear coming out of your mouth things that you yourself don’t like at all, things that shatter your self-image as a fair, kind, cool, attractive, in-control, funny, likable person. Something realer than likability has come out in you, and suddenly you’re having an actual life.

Suddenly there’s a real choice to be made, not a fake consumer choice between a BlackBerry and an iPhone, but a question: Do I love this person? And, for the other person, does this person love me?

There is no such thing as a person whose real self you like every particle of. This is why a world of liking is ultimately a lie. But there is such a thing as a person whose real self you love every particle of. And this is why love is such an existential threat to the techno-consumerist order: it exposes the lie.

This is not to say that love is only about fighting. Love is about bottomless empathy, born out of the heart’s revelation that another person is every bit as real as you are. And this is why love, as I understand it, is always specific. Trying to love all of humanity may be a worthy endeavor, but, in a funny way, it keeps the focus on the self, on the self’s own moral or spiritual well-being. Whereas, to love a specific person, and to identify with his or her struggles and joys as if they were your own, you have to surrender some of your self.

The big risk here, of course, is rejection. We can all handle being disliked now and then, because there’s such an infinitely big pool of potential likers. But to expose your whole self, not just the likable surface, and to have it rejected, can be catastrophically painful. The prospect of pain generally, the pain of loss, of breakup, of death, is what makes it so tempting to avoid love and stay safely in the world of liking.

And yet pain hurts but it doesn’t kill. When you consider the alternative — an anesthetized dream of self-sufficiency, abetted by technology — pain emerges as the natural product and natural indicator of being alive in a resistant world. To go through a life painlessly is to have not lived. Even just to say to yourself, “Oh, I’ll get to that love and pain stuff later, maybe in my 30s” is to consign yourself to 10 years of merely taking up space on the planet and burning up its resources. Of being (and I mean this in the most damning sense of the word) a consumer.

When I was in college, and for many years after, I liked the natural world. Didn’t love it, but definitely liked it. It can be very pretty, nature. And since I was looking for things to find wrong with the world, I naturally gravitated to environmentalism, because there were certainly plenty of things wrong with the environment. And the more I looked at what was wrong — an exploding world population, exploding levels of resource consumption, rising global temperatures, the trashing of the oceans, the logging of our last old-growth forests — the angrier I became.

Finally, in the mid-1990s, I made a conscious decision to stop worrying about the environment. There was nothing meaningful that I personally could do to save the planet, and I wanted to get on with devoting myself to the things I loved. I still tried to keep my carbon footprint small, but that was as far as I could go without falling back into rage and despair.

BUT then a funny thing happened to me. It’s a long story, but basically I fell in love with birds. I did this not without significant resistance, because it’s very uncool to be a birdwatcher, because anything that betrays real passion is by definition uncool. But little by little, in spite of myself, I developed this passion, and although one-half of a passion is obsession, the other half is love.

And so, yes, I kept a meticulous list of the birds I’d seen, and, yes, I went to inordinate lengths to see new species. But, no less important, whenever I looked at a bird, any bird, even a pigeon or a robin, I could feel my heart overflow with love. And love, as I’ve been trying to say today, is where our troubles begin.

Because now, not merely liking nature but loving a specific and vital part of it, I had no choice but to start worrying about the environment again. The news on that front was no better than when I’d decided to quit worrying about it — was considerably worse, in fact — but now those threatened forests and wetlands and oceans weren’t just pretty scenes for me to enjoy. They were the home of animals I loved.

And here’s where a curious paradox emerged. My anger and pain and despair about the planet were only increased by my concern for wild birds, and yet, as I began to get involved in bird conservation and learned more about the many threats that birds face, it became easier, not harder, to live with my anger and despair and pain.

How does this happen? I think, for one thing, that my love of birds became a portal to an important, less self-centered part of myself that I’d never even known existed. Instead of continuing to drift forward through my life as a global citizen, liking and disliking and withholding my commitment for some later date, I was forced to confront a self that I had to either straight-up accept or flat-out reject.

Which is what love will do to a person. Because the fundamental fact about all of us is that we’re alive for a while but will die before long. This fact is the real root cause of all our anger and pain and despair. And you can either run from this fact or, by way of love, you can embrace it.

When you stay in your room and rage or sneer or shrug your shoulders, as I did for many years, the world and its problems are impossibly daunting. But when you go out and put yourself in real relation to real people, or even just real animals, there’s a very real danger that you might love some of them.

And who knows what might happen to you then?

A small research arm of the U.S. government's intelligence establishment wants to understand how speakers of Farsi, Russian, English, and Spanish see the world by computationally evaluating through their use of metaphors.That's right, metaphors, like Shakespeare's famous line, "All the world's a stage" or more subtly, "The darkness pressed in on all sides." Every speaker in every language in the world uses them effortlessly, and the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity wants know how what we say reflects our worldviews. They call it The Metaphor Program, and it is a unique effort within the government to deal with how we words.

"The Metaphor Program will exploit the fact that metaphors are pervasive in everyday talk and reveal the underlying beliefs and worldviews of members of a culture," declared an open solicitation for researchers released last week. A spokesperson for IARPA declined to comment at the time.

IARPA wants some computer scientists with experience in processing language in big chunks to come up with methods of pulling out a culture's relationship with particular concepts."They really are trying to get at what people think using how they talk," Benjamin Bergen, a cognitive scientist at the University of California, San Diego, told me. Bergen is one of a dozen or so lead researchers who are expected to vie for a research grant that could be worth tens of millions of dollars million of five years, if the team scan show progress towards automatically tagging and processing metaphors across languages."IARPA grants are big," said Jennifer Carter of Applied Research Associates, a 1,600-strong research company that may throw its hat in the Metaphor ring after winning a lead research spot in a separate IARPA solicitation. "Generally what happens is that four or five teams will get $20 million each and there will be a 'downselect' each year, so maybe only one team will get money for the whole five years," Carter said.

All this to say: The Metaphor Program may represent a 9-figure investment by the government in understanding how people use language. But that's because metaphor studies aren't light or frilly and IARPA isn't afraid of taking on unusual sounding projects if they think they might help intelligence analysts sort through and decode the tremendous amounts of data pouring into their minds.

In a presentation to prospective research "performers," as they're known, The Metaphor Program's manager, Heather McCallum-Bayliss gave the following example of the power of metaphors in political discussions. Her slide reads:

Metaphors shape how people think about complex topics and can influence beliefs. A study presented participants with a report on crime in a city; they were asked how crime should be addressed in the city. The report contained statistics, including crime and murder rates, as well as one of two metaphors, CRIME AS A WILD BEAST or CRIME AS A VIRUS. The participants were influenced by the embedded metaphor...McCallum-Bayliss appears to be referring to a 2011 paper published in the PLoS ONE, "Metaphors We Think With: The Role of Metaphor in Reasoning," lead authored by Stanford's Paul Thibodeau. In that case, if people were given the crime-as-a-virus framing, they were more likely to suggest social reform and less likely to suggest more law enforcement or harsher punishments for criminals. The differences generated by the metaphor alternatives were "were larger than those that exist between Democrats and Republicans, or between men and women," the study authors noted.

Every writer (and reader) knows that there are clues to how people think and ways to influence each other through our use of words. Metaphor researchers, of whom there are a surprising number and variety, have formalized many of these intuitions into whole branches of cognitive linguistics using studies like the one outlined above (more on that later). But what IARPA's project calls for is the deployment of spy resources against an entire language. Where you or I might parse a sentence, this project wants to parse, say, all the pages in Farsi on the Internet looking for hidden levers into the consciousness of a people.

"The study of language offers a strategic opportunity for improved counterterrorist intelligence, in that it enables the possibility of understanding of the Other's perceptions and motivations, be he friend or foe," the two authors of Computational Methods for Counterterrorism wrote. "As we have seen, linguistic expressions have levels of meaning beyond the literal, which it is critical to address. This is true especially when dealing with texts from a high-context traditionalist culture such as those of Islamic terrorists and insurgents."

In the first phase of the IARPA program, the researchers would simply try to map from the metaphors a language used to the general affect associated with a concept like "journey" or "struggle." These metaphors would then be stored in the metaphor repository. In a later stage, the Metaphor Program scientists will be expected to help answer questions like, "What are the perspectives of Pakistan and India with respect to Kashmir?" by using their metaphorical probes into the cultures. Perhaps, a slide from IARPA suggests, metaphors can tell us something about the way Indians and Pakistanis view the Role of Britain or the concept of the "nation" or "government."

The assumption is that common turns of phrase, dissected and reassembled through cognitive linguistics, could say something about the views of those citizens that they might not be able to say themselves. The language of a culture as reflected in a bunch text on the Internet might hide secrets about the way people think that are so valuable that spies are willing to pay for them.

More Than Words

IARPA is modeled on the famed DARPA -- progenitors of the Internet among other wonders -- and tasked with doing high-risk, high-reward research for the many agencies, the NSA and CIA among them, that make up the American intelligence gathering force. IARPA is, as you might expect, a low-profile organization. Little information is available from the organization aside from a couple of interviews that its administrator, Lisa Porter, a former NASA official, gave back in 2008 to Wired and IEEE Spectrum. Neither publication can avoid joking that the agency is like James Bond's famous research crew, but it turns out that the place is more likely to use cloak and dagger in a sentence than in actual combat with supervillainy.A major component of the agency's work is data mining and analysis. IARPA is split into three program offices with distinct goals: Smart Collection "to dramatically improve the value of collected data from all sources"; Incisive Analysis "to maximize insight from the information we collect, in a timely fashion"; and Safe & Secure Operations "to counter new capabilities implemented by our adversaries that would threaten our ability to operate freely and effectively in a networked world." The Metaphor Program falls under the office of Incisive Analysis and is headed by the aforementioned McCallum-Bayliss, a former technologist at Lockheed Martin and IBM, who co-filed several patents relating to the processing of names in databases.

Incisive Analysis has put out several calls for other projects. They range widely in scope and domain. The Babel Program seeks to "demonstrate the ability to generate a speech transcription system for any new language within one week to support keyword search performance for effective triage of massive amounts of speech recorded in challenging real-world situations." ALADDIN aims to create software to automatically monitor massive amounts of video. The FUSE Program is trying to "develop automated methods that aid in the systematic, continuous, and comprehensive assessment of technical emergence" using the scientific and patent literature.

All three projects are technologically exciting, but none of those projects has the poetic ring nor the smell of humanity of The Metaphor Program. The Metaphor Program wants to understand what human beings mean through the unvoiced emotional inflection of our words. That's normally the work of an examined life, not a piece of spy software.

There is some precedent for the work. It comes from two directions: cognitive linguistics and natural language processing. On the cognitive linguistic side, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson of the University of California, Berkeley did the foundational work, notably in their 1980 book, Metaphors We Live By. As summarized recently by Zoltán Kövecses in his book, Metaphor: A Practical Introduction, Lakoff and Johnson showed that metaphors weren't just the devices of writers but rather "a valuable cognitive tool without which neither poets nor you and I as ordinary people could live."

In this school of cognitive linguistics, we need to use more embodied, concrete domains in order to describe more abstract ones. Researchers assembled the linguistic expressions we use like "That class gave me food for thought" and "His idea was half-baked" into a construct called a "conceptual category." These come in the form of awesomely simple sentences like "Ideas Are Food." And there are whole great lists of them. (My favorites: Darkness Is a Solid; Time Is Something Moving Toward You; Happiness Is Fluid In a Container; Control Is Up.) The conceptual categories show that humans use one domain ("the source") to describe another ("the target"). So, take Ideas Are Food: thinking is preparing food and understanding is digestion and believing is swallowing and learning is eating and communicating is feeding. Put simply: we import the logic of the source domain into the target domain.

Below, you can check out how one, "Ideas Are Food," is expressed, or skip past the gallery to the rest of the story.

The main point here is that metaphors, in this sense, aren't soft or literary in any narrow sense. Rather, they are a deep and fundamental way that humans make sense of the world. And unfortunately for spies who want to filter the Internet to look for dangerous people, computers can't make much sense out of sentences like, "We can make beautiful music together," which Google translates as something about actually playing music when, of course, it really means, "We can be good together." (Or as the conceptual category would indicate it: "Interpersonal Harmony Is Musical Harmony.")While some of the underlying structures of the metaphors -- the conceptual categories -- are near universal (e.g. Happy Is Up), there are many variations in their range, elaboration, and emphasis. And, of course, not every category is universal. For example, Kövecses points to a special conceptual category in Japanese centered around the hara, or belly, "Anger Is (In The) Hara." In Zulu, one finds an important category, "Anger Is (Understood As Being) In the Heart," which would be rare in English. Alternatively, while many cultures conceive of anger as a hot fluid in a container, it's in English that we "blow off steam," a turn of phrase that wouldn't make sense in Zulu.

These relationships have been painstakingly mapped by human analysts over the last 30 years and they represent a deep culturolinguistic knowledge base. For the cognitive linguistic school, all of these uses of language reveal something about the way the people of a culture understand each other and the world. And that's really the target of the metaphor program, and what makes it unprecedented. They're after a deeper understanding of the way people use words because the deep patterns encoded in language may help intelligence analysts understand the people, not just the texts.

For Lakoff, it's about time that the government started taking metaphor seriously. "There have 30 years of neglect of current linguistics in all government-sponsored research," he told me. "And finally there is somebody in the government has managed to do something after many years of trying."

UC San Diego's Bergen agreed. "It's a totally unique project," he said. "I've never seen anything like it."

But that doesn't mean it's going to be easy to create a system that can automatically deduce what Americans' biases about education from a statement like "The teacher spoon-fed the students."

Lakoff contends that it will take a long, sustained effort by IARPA (or anyone else) to complete the task. "The quick-and-dirty way" won't work, he said. "Are they going to do a serious scientific account?"

Building a Metaphor Machine

The metaphor problem is particularly difficult because we don't even know what the right answers to our queries are, Bergen said."If you think about other sorts of automation of language processing, there are right answers," he said. "In speech recognition, you know what the word should be. So you can do statistical learning. You use humans, tag up a corpus and then run some machine learning algorithms on that. Unfortunately, here, we don't know what the right answers are."

For one, we don't really have a stable way of telling what is and what is not metaphorical language. And metaphorical language is changing all the time. Parsing text for metaphors is tough work for humans and we're made for it. The kind of intensive linguistic analysis that's made Lakoff and his students (of whom Bergen was one) famous can take a human two hours for every 500 words on the page.

But it's that very difficulty that makes people want to deploy computing resources instead of human beings. And they do have some directions that they could take. mes Martin of the University of Colorado played a key role in the late 1980s and early 1990s in defining the problem and suggesting a solution. Martin contended "the interpretation of novel metaphors can be accomplished through the systematic extension, elaboration, and combination of knowledge about already well-understood metaphors," in a 1988 paper.

What that means is that within a given domain -- say, "the family" in Arabic -- you can start to process text around that. First you'll have humans go in and tag up the data, finding the metaphors. Then, you'd use what they learned about the target domain "family" to look for metaphorical words that are often associated with it. Then, you run permutations on those words from the source domain to find other metaphors you might not have before. Eventually you build up a repository of metaphors in Arabic around the domain of family.

Of course, that's not exactly what IARPA's looking for, but it's where the research teams will be starting. To get better results, they will have to start to learn a lot more about the relationships between the words in the metaphors. For Lakoff, that means understanding the frames and logics that inform metaphors and structure our thinking as we use them. For Bergen, it means refining the rules by which software can process language. There are three levels of analysis that would then be combined. First, you could know something about the metaphorical bias of an individual word. Crossroads, for example, is generally used in metaphorical terms. Second, words in close proximity might generate a bias, too. "Knockout in the same clause as "she" has a much higher probability of being metaphorical if it's in close proximity to 'he,'" Bergen offered as an example. Third, for certain topics, certain words become more active for metaphorical usage. The economy's movement, for example, probably maps to a source domain of motion through space. So, accelerate to describe something about the economy is probably metaphorical. Create a statistical model to combine the outputs of those three processes and you've got a brute force method for identifying metaphors in a text.

In this particular competition, there will be more nuanced approaches based on parsing the more general relationships between words in text: sorting out which are nouns and how they connect to verbs, etc. "If you have that information, then you can find parts of sentences that don't look like they should be there," Bergen explained. A classic kind of identifier would be a type mismatch. "If I am the verb smile, I like to have a subject that has a face," he said. If something without a face is smiling, it might be an indication that some kind of figurative language is being employed.

From these constituent parts -- and whatever other wild stuff people cook up -- the teams will try to build a metaphor machine that can convert a language into underlying truths about a culture. Feed text in one end and wait on the other end of the Rube Goldberg software for a series of beliefs about family or America or power.

We might never be able to build such a thing. Indeed, I get the feeling that we can't, at least not yet. But what if we can?

"Are they going to use it wisely?" Lakoff posed. "Because using it to detect terrorists is not a bad idea, but then the question is: are they going to use it to spy on us?"

I don't know, but I know that as an American I think through these metaphors: Problem Is a Target; Society Is a Body; Control Is Up.

Is that a Long Island in your pocket, or are you just happy to see me?

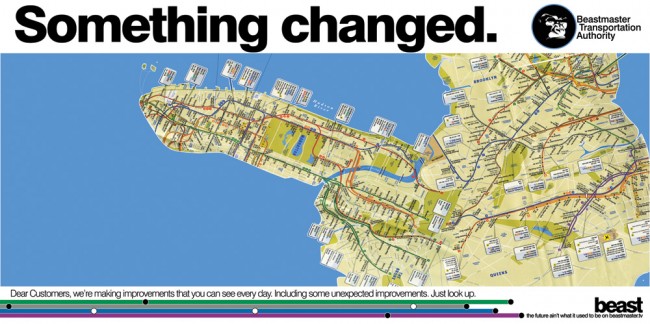

Something has changed indeed.

Emerging street artist Beast made a few not-so-subtle alterations to the map and posted them at subway entrances around the city last week. Props to him for taking the Manhattan as phallus motif a step further and for poking (no pun intended) fun at the MTA’s silly new ad campaign.

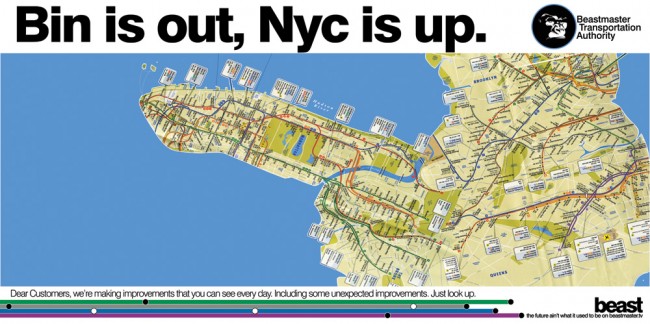

Another version of the faux-sign evokes recent events.

Tourists continued using the maps, unhindered by the text tilted 100 degrees.

Something’s different here. Ah yes! They changed the color of the water!

by Solve Media